I’ve been thinking a lot about the Internet’s burgeoning shift towards AI, my personal position as a diehard technologist and also an analog curator, and this Catherine Shannon essay titled “your phone is why you don’t feel sexy.” I also recently read Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist by Liz Pelly, who I also interviewed for the newsletter (that profile should be out next week). At the risk of over-exploring my ideas on the topic, I wanted to dedicate a broader issue of Record Store to the complicated relationship between curation and technology.

I wrote earlier this year about what I see as a taste crisis—people being so impacted by the algorithm that they can no longer tell what they like and dislike. In her book, Liz writes multiple chapters about the degradation of the Spotify user experience and the company’s insidious push towards passivity, which benefits them financially and culturally. In turn, this shift across the user base starts to alter the music landscape itself, an object becoming so massive it starts to affect the gravitational field. The change isn’t just inherent to Spotify; people, especially young people, jump from trend to trend—fashion, linguistics, architecture, design—as they’re force fed content via social and traditional media designed to make them less discerning, less opinionated.

I always say I was born in the right generation; I love the Internet, I love memes and public archives, I love texting my friends and having what I call content-rich relationships. I love sending demos to Blake so we can have a band that is technically based in two cities. And I love Spotify, as much as it hurts to say it—the platform allowed me to access and catalog music to such a granular extent that I see it as a secondary diary, spanning my entire adult life. The ease with which I can try something new, with virtually zero barrier to entry, has made me a more adventurous and open listener. But I was habituated to streaming after being habituated to music, not the other way around, and I think a reversed or simultaneous experience could have very well made me helpless to discovery, as many people I’ve spoken with about Spotify and their music taste feel.

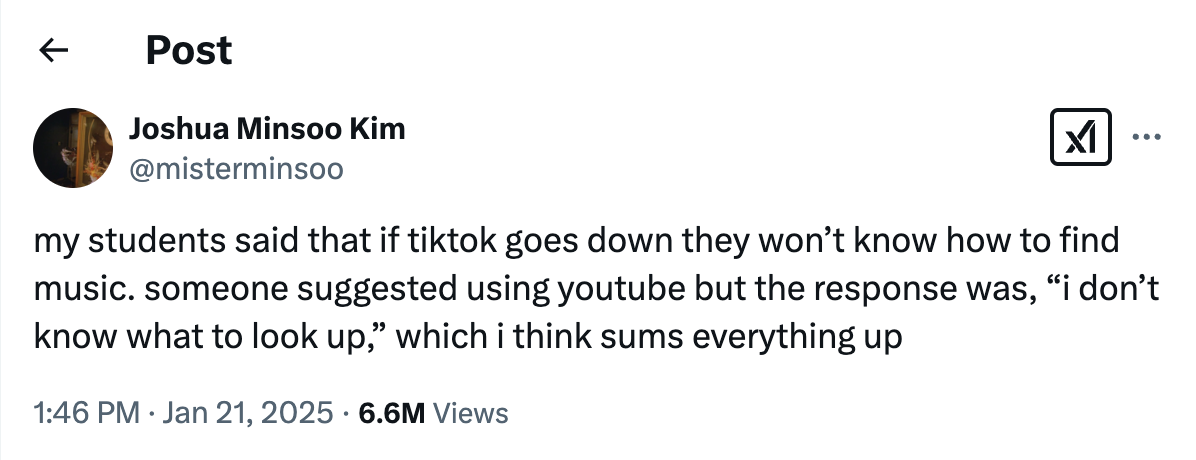

I’ve thought about this tweet basically everyday since culture writer Joshua Minsoo Kim posted it—personalization and algorithmic listening has made it such that listeners’ muscle of active discovery either atrophies or worse, is never developed, as is the case with his students. Liz Pelly touches on this issue in Mood Machine, but the arbitrary micro-genres created by Spotify for the sake of further isolating a user in their own preferences (what is bubblegrunge? Be serious) have the effect of hamstringing listeners when it comes to seeking out new music—what would they search? Spotify, if you don’t use the algorithmically generated playlists, is like being in a library with the lights off, groping around blindly, unable to read the spines.

More and more, the technology that facilitated my own development as an artist and the art itself seem to be at odds. As Spotify moves to demonetize smaller artists and Bandcamp gets bought and sold by union-busting mega-corporations, it seems like the world is in need of a new method of accessing and cherishing (as opposed to consuming) music. I’ve asked many people recently, in interviews for this newsletter as well as in my personal life, if they think that the broader listener-base of people accustomed to daylists and daily mixes are ready for, or will ever be ready for, a method of listening that requires work. I’ve asked programmers around me why it seems that there are opportunities to use technology to help artists be fairly compensated for their work and time but no action towards such change (capitalism, obviously). I’ve asked myself why I can clearly state my values around music, but can’t seem to make the jump to another platform or no platform at all just yet.

In her essay, Catherine Shannon states: “Today, everyone and everything is always available, and there’s nothing less sexy than that. There’s no chase. Our phones don’t allow us time to dwell, and they don’t allow us time to yearn.” Finding the joy in discovery, in the pursuit of discovery, again can save us—I truly believe that. The difference between picking something up instead of having it handed to you is vital, an act of agency that translates directly to the active decision making skills that shape ethics and values. It also contributes to this feeling of sexiness that Catherine Shannon describes, a power over your own life and gratification in your labor that brings meaning to your engagement with art and culture beyond consumption. Your taste is yours to make.

Reading list:

“Your phone is why you don’t feel sexy” by Catherine Shannon

Deep Listening by Pauline Oliveros

How Music Got Free by Stephen Witt

IN CONVERSATION WITH: Mike Pollard (Katie Chiou for Archetype)

Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist by Liz Pelly

I’m grateful that I came up in a time that required me to be active if I wanted to discover new music. Sure, it was more work, and perhaps I’ve got it too easy right now (at the risk of getting lazy). Although I still have a heavy reliance on Spotify (through non-Spotify new music playlists like NPR and Line of Best Fit) I still explore other avenues like Bandcamp and music review sites and, increasingly over the last 18 months, recommendations read right here on Substack.

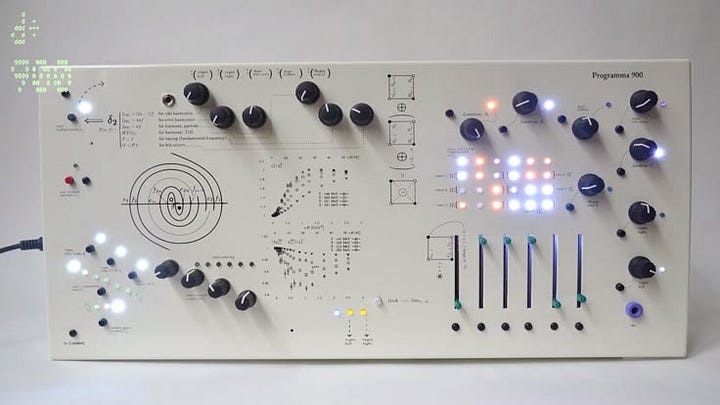

I like to discover music from

- hearing records from friends' collections, that they've chosen to play for me;

- reading reviews by opinionated aesthetes;

- listening to idiosyncratic human DJs spin records on independent radio; and,

- hearing artists playing live at festivals.